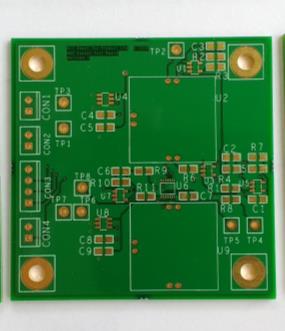

As mentioned in the previous blog, we put in a lot of preparation work over summer 2018 in order to be able to quickly start work on the Pollution Guardian project and de-risk certain areas. One of the first items to be actioned was the creation of a custom circuit board to explore the performance of our selected, affordable Nitrogen Dioxide (NO2) gas sensors and the type of electronics needed to setup, amplify and filter the output of these sensors. We called it our “bench test” circuit board as we thought it would only get used indoors on the bench..

With the bench test board, we designed a couple of options for the electronics solution:

- to provide a backup option, in case the one circuit failed to perform

- provide us alternate options based on relative performance

- to enable optimisation of the bill of materials cost

Designing & making the circuits went relatively smoothly, but it is not until you receive circuits that you can really see what is going on. Some mistakes we discovered quickly, whilst others took a period to debug. Mostly our mistakes were due to the misinterpretation of and assumptions on the component specifications; our first solutions to these issues actually went on to compound our problems.

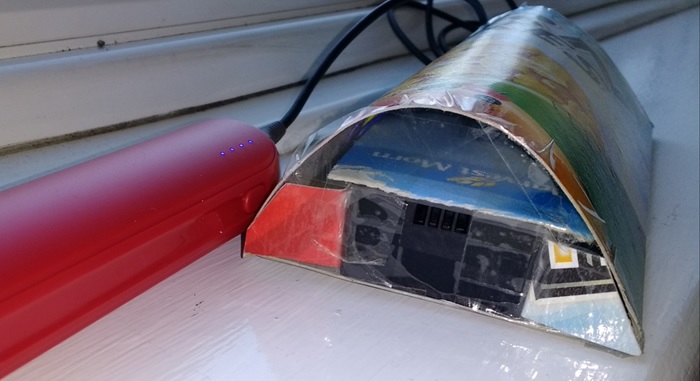

After a period of investigation and debugging, we were finally able to identify and solve the underlying issue. As part of this work, we lashed these prototype circuits together with an off-shelf development board (TI cc2640R2) all contained in a cereal packet wrap for protection. We called our first units Dougal & Zebedee and took them out of the lab and into the car:

What we found when we started testing out the units was that whilst our units appeared quite sensitive to temperature change, they were actually capable of detecting low levels of NO2 inside the car.

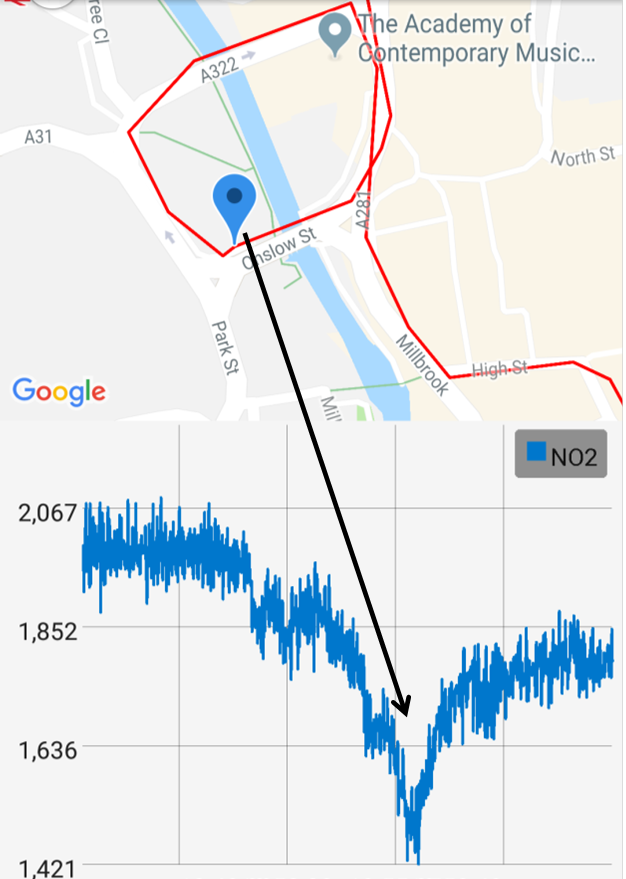

The picture below shows a trace of NO2 measurements whilst traversing the one way gyratory system in the centre of Guildford – note that a decreasing level on the graph trace implies a higher NO2 concentration:

So, at the conclusion of our cardboard proto work, we knew we had the right potential sensitivity toward NO2 which we could work with on the next prototype to calibrate and try to get consistent between test units.